To Consider

Why would you take by force from us that which you can obtain by love? Wahunsonacock, a Powhatan Leader

There are several articles on this page and different points of view.

VOICES THROUGH HISTORY

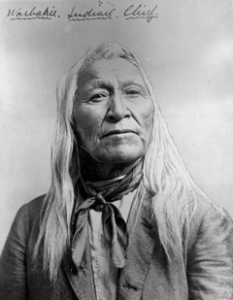

“…Shoshoni Chief Washakie doubtless spoke for many Natives when he remarked in 1878: “The white man’s government promised that if we, the Shoshones, would be content with the little patch allowed us, [it] would keep us well supplied with everything necessary to comfortable living, and would see that no white man should cross our borders for our game, or for anything that is ours. But it has not kept its word! The white man kills our game, captures our furs, and sometimes feeds his herds upon our meadows. And your great and mighty government…does not protect us in our rights. It leaves us with-out the promised seed, without tools for cultivating the land, without implements for harvesting our crops, without breeding animals better than ours, without the food we still lack….I say again, the government does not keep its word! And so after all we can get by cultivating the land, and by hunting and fishing, we are sometimes nearly starved, and go half naked, as you see us! Knowing all this, do you wonder, sir, that we have fits of desperation and think to be avenged?”…” Quoted in Ibid., 456. http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/content/files/ hayes_historical_journal/usindianpolicyhhj.htm#21 Photo;http://www.windriverhistory.org/ exhibits/washakie_2/images/washakie.jpg

“…Shoshoni Chief Washakie doubtless spoke for many Natives when he remarked in 1878: “The white man’s government promised that if we, the Shoshones, would be content with the little patch allowed us, [it] would keep us well supplied with everything necessary to comfortable living, and would see that no white man should cross our borders for our game, or for anything that is ours. But it has not kept its word! The white man kills our game, captures our furs, and sometimes feeds his herds upon our meadows. And your great and mighty government…does not protect us in our rights. It leaves us with-out the promised seed, without tools for cultivating the land, without implements for harvesting our crops, without breeding animals better than ours, without the food we still lack….I say again, the government does not keep its word! And so after all we can get by cultivating the land, and by hunting and fishing, we are sometimes nearly starved, and go half naked, as you see us! Knowing all this, do you wonder, sir, that we have fits of desperation and think to be avenged?”…” Quoted in Ibid., 456. http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/content/files/ hayes_historical_journal/usindianpolicyhhj.htm#21 Photo;http://www.windriverhistory.org/ exhibits/washakie_2/images/washakie.jpg

*************************************************************************************************

The Indian was frugal in the midst of plenty. When the buffalo roamed the plains in multitudes he slaughtered only what he could eat and these he used to the hair and bones. Luther Standing Bear, Lakota

We will not have the wagons which make a noise in the hunting grounds of the buffalo. If the palefaces come farther into our land, there will be scalps of your brethren in the wigwams of the Cheyennes. I have spoken. Roman Nose, Cheyenne, 1866

Only seven years ago we made a treaty by which we were assured that the buffalo country should be left to us forever. Now they threaten to take that away from us. My brothers, shall we submit or shall we say to them: “First kill me before you take possession of my …land…” Sitting Bull, Hunkpapa

I can remember when the bison were so many that they could not be counted, but more and more wasichus came to kill them until there were only heaps of bones scattered where they used to be. The wasichus did not kill them to eat; they killed them for the metal that makes them crazy, and they took only the hides to sell. Sometimes they did not even take the hides, only the tongues; and I have heard that fire-boats came down the Missouri River loaded with dried bison tongues. Black Elk, Lakota

In my youthful days, I have seen large herds of buffalo on these prairies, and elk were found in every grove, but they are here no more, having gone towards the setting sun. Shabonee, Potawatomi, 1827

I see no longer the curling smoke rising from our lodge poles. I hear no longer the songs of the women as they prepare the meal. The antelope are gone; the buffalo wallows are empty. Only the wail of the coyote is heard. Plenty Coups, Sioux, 1909

My nation was ignored in your history textbooks…they were little more important in the history of Canada than the buffalo that ranged the plains. Dan George, Coast Salish From: Journal #3011 from sdc 12.24.12

On telling Native people to just “get over it” or why I teach about the Walking Dead in my Native Studies classes…

So a friend of mine wrote me a message on Facebook that went a little like this:

how the heck do you get through to someone that thinks natives need to just get over it.I started writing him back and then realized that on this day (a day where I should be grading and preparing for final exams) this question sparked something in me and suddenly I was writing him a blog entry. I decided I would both send him my somewhat epic response and also – post it here.

Then I’ll start getting ready for finals. I swear!

Question: how the heck do you get through to someone that thinks natives need to just get over it.

Answer: Shake them? I never advocate shaking people, but maybe something is loose in there. Tell them to take a Native American Studies Course (it ain’t cheap, but it’s worth it). But if I’m being honest, lately, when this comes up (and isn’t it telling that it comes up often enough that I can begin with “lately” instead of “well the last time, a long time ago, man I can barely remember that time”) I like to tell them about The Walking Dead. I must take a moment here to tell you all *Spoiler Alert.* That’s right. I’m going to put it all out there. I’m going to tell you about all the nitty gritty of the Walking Dead that I can muster in one blog entry. It is ALL going to be one massive *Spoiler Alert* especially if you haven’t had the opportunity to watch all the past seasons on Netflix yet because you have a life and there is never the perfect moment to sit down and watch a slow moving, somewhat depressing, not always entertaining indictment of humanity in the midst of a zombie-apocalypse and the end of the world as we know it. *Spoiler Alert*

There is this one scene in this season of the Walking Dead where some of the characters are talking. Actually that’s most scenes, there is a WHOLE lot of talking in this show, but I digress. In this scene, we find out the “questions” that the leader of “the group” (Rick) asks to people when he meets them to determine if he can bring them in to their safe space and make them a

part of the group. How many walkers (zombies, for those who don’t watch the show) have you killed? How many people have you killed? Why? But there is a fourth question that comes up a lot in the show that isn’t a part of this list. Rick asks it a few times in this season, and others in their own conversations are essentially asking it as well. Do you think we can come back from this? Will we be able to move on after we have had to live through and do horrible things? Whathappens to our humanity? It’s something that is explored throughout the season, especially by the “leader” (de facto, not always, sometimes farmer, often confused, very sweaty “leader”) Rick and in the end he makes a grand speech that yes, yes we can come back from this.

“We can come back,” he says. “We all can change.” (Season 4, Episode 8) Right after that his friend is beheaded by the Governor, a guy who CANNOT change, an all out shooting war starts, a bunch of people die and run away and there is the possibility that Rick’s

baby has been eaten by zombies. But you know… hope.

Anyway, Indians. When I started watching the Walking Dead I immediately thought about Indians. And when people tell me “Man, Indians, they are always going on and on about genocide and stuff and they should just get over it” I often pause and say “Well, consider the Walking Dead…”

Lawrence Gross (he’s a scholar and a Native person) talks about “Post Apocalypse Stress Syndrome” where he says that Native American people have “seen the end of our world” which has created “tremendous social stresses.” California Indians often refer to the Mission System and the Gold Rush as “the end of the world.” What those who survived experienced was both the “apocalypse” and “post apocalypse.” It was nothing short of zombies running around trying to kill them. Think about it. Miners (who were up in Northern California, where I am from) thought it was perfectly fine to have “Indian hunting days” or organize militias specifically to kill Indian people. These militias were paid. They were given 25 cents a scalp and $5 a head. (In 1851 and 1852 the

state of California paid out close to $1 million for the killing of Indians…) In effect, for a long time in California, if you were an Indian person walking around, something or someone might just try to kill you. They were hungry for your scalp and your head. They had no remorse. There was no reasoning with them. And there were more of them then there was of you. (Zombies. But even worse, living, breathing, people Zombies. Zombies who could look at you and talk to you and who were supposed to be human. Keep that in mind. The atrocities of genocide during this period of time, they were not committed by monsters — they were committed by people. By neighbors. By fathers, sons, mothers, and daughters.) In the Walking Dead the survivors resort to hiding. Sometimes they go in to town and barely survive an attack as they try to steal food or gather supplies. Sometimes they turn on each other. Sometimes they lose people they are close to. Sometimes they have to kill to stay alive. The world is in chaos. Everyone probably has high blood pressure. They probably don’t sleep much. They probably don’t get the proper nutrition. They probably get sick and die of the flu, because it’s hard to get medicine and rest and get better – when something is out there constantly coming after you, trying to kill you and everyone you care about. (Zombie-pocalypse sounds eerily similar to California Indian history…)

How long until you tell those zombie-pocalypse folks to just “get over it already?” How long until you tell them “it was a long time ago?” How long until you tell them “it’s not worth talking about. It doesn’t affect me! I wasn’t there.” How long until you pretend like it’s not still a part of future generations? How long until you try to erase that the zombie-pocalypse ever happened? I asked someone this question once and they said “well, it’s never the same after that. That becomes a part of who everyone is. It doesn’t go away. I mean it’s the freaking end of the world. You can’t just pretend like that never happened.”

Exactly.#2: I like to tell them about Carl’s great grandchildren. Carl is Rick’s kid in the Walking Dead. At first I hated him because he’s dumb. He’s in a zombiepocalypse and he’s all wandering off by himself and acting like he can just hang out and not be useful. But then he ends up becoming a bad ass who likes to make decisions, unlike his Dad, who really only makes the decision that he will no longer make any decisions. *Leadership* Anyway, if you think about it — Carl, who is living through the end of the world, which for him means loss, suffering, shooting some kid in the head because he came into his camp, having to kill his mother after she gave birth to his sister, watching his father go crazy for a period of time, getting shot, and having to watch his Dad kill his other father figure (stupid Shane), getting shot in the stomach, and finally thinking that his little baby sister has been eaten by zombies (I say thinking, because I’m convinced that somebody rescued her) – well Carl is my Great Grandfather. That’s right. That’s how close it is. My Great-Grandfather was living through the genocide of California Native peoples. My Great-Grandfather had to hide from Russian Soldiers who were coming for him. He tells stories about using reeds to breathe under a sand pit so that people wouldn’t find him. He was taken to Boarding School, he ran away and spent months in jail as a kid. He was hunted by bounty hunters. His Uncle was shot several times, people in his tribe were killed. Lot’s of people’s Grandparents and Great-Grandparents have stories like this. We are not that far away from when Native people were being massacred, in the name of our “great state” because “it was the only Christian thing to do.” Also – did you know they recently completed a study which showed that your ancestors experiences leave an epigenetic mark on your genes? Or as Dan Hurley from Discover Magazine put it: Your ancestors’ lousy childhoods or excellent adventures might change your personality, bequeathing anxiety or resilience by altering the epigenetic expressions of genes in the brain. Exactly.

#3: I like to tell them that I agree with them. Wait? What? And I just nod. “Yep, I agree. We should get over it. In fact, I am over it.”

Wait? What? Well I’m over it. I don’t like to speak for all Native people in the universe because that’s not fair, and we’ve never been able to come to a consensus at the meetings we have where we decide how all Native people feel about things. (We do not have these meetings, by the way, there are lots of Native people, we are very different from each other, that meeting would be huge, I would

probably go because there would be lots of good food and laughter.) But I am over it. I am over the federal government trying to pass policy and laws that sanction and legalize genocide, slavery and removal of Indian people. I am over the legalized attempts toseize land and rights from Native peoples through racist, flawed, discriminatory, and frankly imaginary legal doctrines like the Doctrine of Discovery.

I am over the Doctrine of Discovery. I am over plenary power. I am over the taking of Indian children away from their families and placing them in ‘good homes’ which implies that Indian homes are not good enough. I am over the fact that at most colleges Native students are less than 1% of the population but in certain states Native peoples are between 4-6% of the prison population. I am over that Native women are more likely to be raped than any other group in the United States. I am over that close to 90% of the population of Native people in California were killed during this historical time period and yet we do not have a monument or requirement to learn about this in schools. We do however have a monument and requirement to learn about Father Junipero Serra, who liked to beat and starve Native people. I am over models dressed like Indian women on runways while sticking out their tongues. I am over t-shirts that portray Native people as permissive of drug use and music videos that promote Native women as permissive of being oogled over while tied up to a wall. I am over policies that keep Native people from practicing their religion and keep Native people from tending to and being responsible for the land. I am over trying to find a benign/objective way to say slavery, genocide, holocaust, murder, massacre, slaughter, rape, abuse, violence and pain because people don’t like to hear about the true California history. I am over the vanishing Indian. I am over the same old story that gets told, the one where we would rather be dead, the one where we were fading away, the one where we have bigger problems than history, the one where the past is the past. I am over that telling me to “get over it” asks me to pretend that these things are not still happening. I am over pretending that Native people aren’t still dealing with many issues that have their roots in genocide, especially in California. I am over erasing the past at the behest of people who would rather ignore it, then have to also accept and “get over it.”

I am over it. That’s why I won’t stop talking about it. That’s why I CAN talk about it. That’s why I have to talk about it. Ask yourself what it means to be “over it.” Because to me, this does not mean “never ever mention it” again. To me this means, now we can really talk about it, all of it. And we should. When we stop talking, when we stop remembering, when we stop honoring that past, we become ignorant of how that past is the present, is the future. We cannot be complicit in erasing the past by “getting over it.” In these words, when we speak to our survival, we are sending strength to those who fought, bled, died, and refused to “get over” what was happening to them. We also refuse to accept that it can, should, or will happen to us. We stand up. We fight.We owe it to them to continue to fight just as hard as they did. Our ancestors will feel it “back then” like we feel it now. They will know “back then” that we are here because we didn’t just “get over it.” They must have known of us, their future. They must have thought of us, their grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great grandchildren. Some Native people say they think of Seven Generations when they do things. When our ancestors were sitting together, talking, trying to figure out how to survive this “end of the world” they must have said to each other “Do you think we can come back from this?” And they must have thought about the future generations (like us). Perhaps they saw in the fire a group of us laughing together, perhaps they dreamed about us, singing together, dancing together and they knew the answer… “yes, we will.” Now it is up to us to help our next seven generations to remember. We can all “get over it” but we will never forget.

******************************

Hating the American Indian, A Time Honored Tradition – The Indian Wars are Not Over Lawrence Sampson Nashville Public Policy Examiner January 11, 2014

It’s always there. It hides well and often appears to be a bygone product of history but make no mistake, it’s presence is as much a fact as the sunrise in the east. It only takes a whisper, one event or a single issue to peel back the camouflage of serenity and reveal it in all its glory. It’s apparently a permanent part of the American psyche despite all thoughts to the contrary. Don’t look now, because it is once again on the loose and running wild all over the continent. What is “it” you ask? Why it’s anti-Indian sentiment, the lesser known brother of racism that most Americans would rather not discuss but the First Nations of this country know intimately.

The funny thing is, in talking to the average American, there appears to be a commonly expressed affinity for American Indian people and culture. I’ve often been told by white Americans that “you Indians sure got a raw deal”. One can hardly peruse the romance novel section of your local bookstore or sample any wild west movie without reading or hearing about the noble people of the past. And that perhaps is the underlying issue, for as soon as people in the present have to learn, up close and personal, that American Indian people are not a forgotten relic of the past, but part of modern vibrant cultures, with human and civil rights that have to be recognized, we get an accurate snapshot of what America really thinks about Indians.

Maybe it’s your local beloved sports team with a racist mascot like the Redskins being pressured to change. Perhaps it’s the revelation that a so-called Christian adoption agency is targeting Indian Country to steal and traffic in Indian babies. From time to time it’s when Indians stand up against the destruction of their land base as we’ve seen in Canada lately. Or possibly, as a small town in Wyoming is learning, that some treaties do matter, will get enforced, and the realization that Indians have legitimate legal claims that sets the pot boiling. Imagine it, American Indians having legal and civil rights. Oh the humanity.

One need only look in the comments section after these or any number of similar stories are run in a local or national publication to get a feel for how many Americans still feel about Indian people, and Indian rights. Safe behind a keyboard, Americans blindly call for a return to scalping, argue that the theft of Indian land are the spoils of war, and that God has decreed the decimation of the Indian race. I mean really you couldn’t make this shit up. It’s like we turn back the pages of history two hundred years every time an Indian stands up for him or herself.

This country has a guilt trip born of a denial of its history. Every American lives their daily live knowing deep down they are the recipient of benefits born of genocide. The fact is, slowly but surely many of these chickens are coming home to roost. Those pesky treaties, the highest law in the land according to the American constitution, are still waiting to be enforced. Whether it be in American or International courts, tribes have been slowly but surely winning righteous victories that even conservative justices cannot completely stop. And along the way, the American redneck or racist or social conservative, choose your own superlative, goes down slowly, always kicking and screaming about the good old days, and those ridiculous “special rights” all Indians seem to have..

So whether you live in Washington D.C. and root for that abomination of a football team mascot, or in Riverton Wyoming and have found you’re subject to aboriginal title, or anywhere else on this continent once populated by millions of Indigenous people, it’s time to ask yourself a question. How do you really feel about the Native American and why? Are you personally willing to take responsibility for historical wrongs, as a beneficiary of genocidal policies? It’s a tough conundrum to be sure, but like it or not every single American has to face these issues sooner or later. This isn’t the good old days where Indians had no voice, and as some have said, we’re not your Indians anymore.

Although the articles below are old, they are still relevant. Surf the web to find newer issues.

“Culture is broader than most people think — fish, wildlife, water, land, are all an integral part. We lose bit by bit because of the loss of resources”. Chad Colter Shoshone Bannock Tribal Fish and Game Director.

Give the light of knowledge

By Louise Engelstad, a member of Canyon Lake Senior Center Writer’s Group. Rapid City Journal – 2.3.05

“Indians are so lazy,” snapped my grandmother. “We can’t get them to come to the program meetings on time!” She shook her head dismissively.

My mother became very still as she looked at her mother thoughtfully. But she didn’t say a word. It was 1957; I was 10 years old and my sister was seven.

The next day, mother presented my sister and me with empty cigar boxes. She had carefully pounded tiny nails evenly spaced across the ends. Then she had wound plain string back and forth from end to end. “What’s this for?” my sister and I asked.

Mother opened a big picture book full of brightly colored rug patterns from the Navajo tribe. “It’s a rug loom,” she said. “We’re going to weave rugs like these. Here’s the yarn; choose your colors!”

Patiently she showed us how to weave over and under the base string on the cigar box looms. “The women made these beautiful rugs to keep their families warm. They spun their own wool from their sheep and used berries and roots to make the colors. Isn’t that amazing?”

My sister and I nodded as we worked on our miniature rugs, trying our best to copy the intricate designs from the book. And we absorbed the real lesson Mother was teaching – the beauty of different cultures.

But my mother wasn’t done yet. I remember another book with a picture of a Lakota chief on its yellow and red cover. “These Indians lived on the Plains in teepees,” mother showed us the pictures. “They used buffalo hides and then rolled the hides up and moved on with these travois. They lived in these in the winter and summer, in the snow and wind.

Using a tray and sand, we modeled a native village complete with a mirror for the lake. We gathered dried sage and juniper for our trees and carefully fashioned teepees from sticks and colored paper. Carefully, we painted the symbols on the outside – lightning, rain, sun. We built tiny drying racks for pemmican and used pebbles for fire rings. We started to wear the color off the cover of the book as we pored over the pictures and stories. And we learned.

And still Mother wasn’t done. We drove out to a buffalo jump near the Madison River. Breathless from the climb up the steep bluff, we peered over the edge. “The men drove the buffalo off the edge, and the women worked to cut the meat and scrape the hides. Every piece had a use,” Mother explained. We looked down at lush green grass growing in the ancient, blood-soaked soil.

One day I asked my mother, “Why did grandmother say the Indians were lazy?”

Mother looked at me thoughtfully. “Your grandmother is an old woman, Louise. When she was a little girl, people were afraid of the Indians. When people are afraid, they sometimes do things they shouldn’t.”

I learned about the deadly cycle of prejudice from my mother’s lessons: don’t be afraid of new things. Rather, learn about new things. Don’t accept others’ opinions about things; rather, learn and form your own opinions. Be careful what you say about people, especially when you don’t know very much about them and their way of life. Don’t judge others; you only show your own insufficient knowledge and ignorance. And try to be compassionate with others’ ignorance; they are usually just afraid. If you can, use old cigar boxes, sand, and a mirror and give the light of knowledge!

On most calendars, October 12th is named “Columbus Day,” celebrating the arrival of the first Europeans to the shores of Hispanola in the Western Hemisphere.

Most indigenous people of the Hemisphere, however, find little to celebrate when they look back on that fateful day in 1492.And for that reason, Native Americans from Canada to Chile have declared October 12th “Indigenous Day,” to bring attention not only to the horrors visited upon indigenous people across the Americas for centuries, but to the ongoing struggle for indigenous rights today, 500 years later, at the dawn of the 21st Century.

THE FIRST AMERICANS

American Indians Open a Massive New Museum in Washington

By Ben A. Franklin |October 15, 2004 Excerpts from The Washington Spectator Vol. 30, #19

Some scholarly speculation has placed the beginning of Native American civilization in about 5,000 B.C., roughly 10,000 years before 1492 A.D., when “Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” Although he was an avid ocean crosser, Columbus made four trans-Atlantic voyages from Spain, but never reached North America. Because he knew the earth was round, he reasoned he could reach “the Indies” by sailing West. He didn’t bargain on running into another, then unknown continent.

There remains disagreement over whether the American Indians came here by boat—and from where is even less certain—or if their founding fathers “fell from the sky,” as some Indian faith purports. But either way they came here more directly than Columbus.

In 1492 Columbus found the Canary Islands and then San Salvador, in the Bahamas, and claimed possession of them for Spain. By 1498 he had discovered, and had become viceroy of, other islands, including Hispaniola, the Leeward Islands, St. Kitts, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and Trinidad and also Honduras. The people he met, he called “Indians.”

Mainland Indians were lucky that Columbus didn’t land there. His shipboard log described the Arawak Indians of the Caribbean that he corralled as so “cowardly” that they could be forced to “work and sow and do everything else that shall be necessary.” That legacy was remembered by 600 protesting Colorado Indians who blocked this year’s Columbus Day parade in Denver, carrying signs that said, “Not Genocide—Celebrate Pride.” More than 200 of them were arrested.

The Vikings, under Leif Ericsson, had discovered some of North America almost 500 years earlier. There is speculation about their landings, but the sites often mentioned include Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, where Viking implements have been found dating back to the year 1000.

In 1585 English colonists landed on Roanoke Island off the North Carolina coast, but ships that returned there in 1590 found the settlement abandoned, apparently because of disease or Indian attacks. The fate of “The Lost Colony” remains one of American history’s enduring mysteries.

The first permanent English settlement in America was built in 1607 on marsh land at Jamestown in southeast Virginia. After surviving some starving winters, the colonists were saved by the arrival of English supply ships.

Tobacco, long grown by the Indians of North America, began to be cultivated by the English settlers there in 1612 for profitable export to the millions who became hooked on it in Europe. Indians also showed the settlers how to grow other exportable crops, including corn, pumpkins, cranberries and tomatoes. And Jamestown became the home of Pocahontas, a daughter of the Pamunkey chief, Powhatan. After first being kidnapped for ransom by English settlers, she was wooed by and married a successful English tobacco planter, a union that brought a period of peace between the colony and Indians.

The celebrated Plymouth settlement in Massachusetts wasn’t established until 1620, when separatist English Puritans aboard the Mayflower failed to reach their destination in Virginia territory and landed at Cape Cod instead. A treaty in 1621 with the Wampanoag Indians brought both sides 50 years of local peace. That was not available in other bloody combats with Indians whom pious whites attacked, believing them to be agents of Satan.

Some of the English settlers of the Massachusetts Bay also profited from the agricultural training given them by a few Indians they befriended and excluded from their harsh judgment of other “savages” and “heathens.” The settlers, who experienced periodic starving times, learned how to plant and harvest corn, squash and beans and were shown the prime areas to fish and hunt. Still, some colonists favored taking over Indian villages, many of which were devastated by exposure to deadly European diseases, and were determined to drive the Indians away…..

West says that “life was not pretty for much of the history of the Native Americans after the European encounter occurred,” bringing to them what he calls “the destructive edge of colonialism.”

But he adds that there are still more than 560 federally recognized tribes in the United States, proving that more than 2 million Native Americans “are still here,” and despite the lack of “mutual respect between non-natives and natives . . . we are not gone.”

EARLY RECOGNITION—The early natives set some lasting examples for the America we all live in today. Benjamin Franklin—and I should say that I am his namesake, not a descendant became so impressed with the Pennsylvania Iroquois’ tribal constitution, which he saw when he was hired as the tribe’s printer, that the Pennsylvania colony named him to his first diplomatic job, its “Indian Commissioner.”

In 1754 Franklin asked a gathering of American colonial delegates—white men—to use the constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy, adopted in a peaceful merger of six combative tribes, as a model for what would eventually, in 1781, be ratified as the U.S. Articles of Confederation. The Iroquois constitution banned the forced entry of private homes by a tribal government, protected freedom of political and religious expression, and imposed the impeachment of corrupt leaders.

Among the long list of other fascinating Indian unknowns, the fact that Articles I, VI and VII of our Constitution are modeled after the Iroquois charter, is a story not widely perceived. Not until 1987 did the U.S. Senate finally pass a resolution stating that the U.S. Constitution had been modeled on American Indian democracy.

LEARNING HISTORY—We all have a lot of homework to do to begin grasping the Native American saga. …. Richard West, the NMAI director, has said that “native peoples want to remove themselves from the category of cultural relics and, instead, be seen and interpreted as peoples and cultures with a deep past that are very much alive today. They want the opportunity to speak directly to our audiences through our public programs, presentations and exhibits—to articulate in their own voices and through their own eyes the meaning of the objects in our collections and their import in native art, culture and history.” ….

“HOW”—Many of us, if not most, recognize that word as the well-known, if hackneyed (by us), greeting of a Native American, the equivalent of “hello.” But how much else is known among us, the heirs of the white invaders who began arriving here five centuries ago, seems minimal.

Growing up in American classrooms and monitoring the radio, television and the movies, we knew about Tonto, the Indian companion of the Lone Ranger, who called him Kemo Sabe—supposedly “he who knows.” On the other hand, Tonto means “dummy” in Spanish—not very nice for your trusted Indian guide. We saw all those John Wayne and other Western movies, many of them replete with savage “redskin” villains. The prejudicial combat is not over yet.

TODAY’S WAR PATHS—The Native American “Trail of Tears” came into being in the 1830s when the U.S. Army enforced the expulsion at rifle point of 16,000 Cherokees from their historic eastern settlements in Georgia, Tennessee and North Carolina, from whence they struggled to prairie land in what became Oklahoma. Some 4,000 Indians died during a deportation that the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson declared would “stink to the world.”

Indian abuse continues today as a fiscal holocaust. It is finally being challenged in court, but the 120-year-old government rip-off of the tribes by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) continues.

The BIA, originally part of the War Department because of the decades of armed combat with warrior tribes, is a notoriously blundering branch of the Interior Department. As we have noted before, its bureaucratic bungles have contributed to its parent agency’s on-the-street Washington title: the “Inferior Department.”

In 1887, as Indian reservations were being broken up and the federal government began leasing or selling the oil, mineral, grazing and timber resources on the Indians’ land to private developers, Congress passed an act allotting modest paybacks to the Indians who were the former occupants.

An ongoing, decade-long tribal lawsuit centers on the BIA, which doles out in small amounts about $500 million a year of the money owed to the Indians. The BIA’s so-called “trust fund,” now loaded with an undistributed $3 billion, has cheated hundreds of thousands of Indians for decades of $137 billion in royalties from the natural resource leases.

In 1994 Congress finally passed the American Indian Trust Reform Management Act, and in court in Washington since 1996 the BIA has been forced to concede that it has mislaid thousands of files and lost track of unpaid beneficiaries. The frequently exasperated federal judge hearing the case, Royce Lamberth, has called the agency’s incompetent conduct “the gold standard for mismanagement by the federal government for more than a century.”

Now comes another astonishing rip-off of Indians—again not widely covered by the media. It involves the shredding of millions of dollars from a few tribes with gambling casino incomes by two operatives of a non-government Washington institution, the lobbying industry.

Two Washington lobbyists, Jack Abramoff and Michael Scanlon, the latter a former aide of House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX), have come under belated public attack for chiseling more than $80 million in lobbying fees from six casino-operating tribes. (DeLay is also under crunching criticism by the House Ethics Committee for other shenanigans.)

The Indian tribes paying the lobbyists expected the two men to protect their casino operations. Instead, they were not only bilked, but as disclosed last month in the first of a series of public hearings by the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, the hired influence-peddlers sent each other a racially denigrating exchange of e-mails referring to their tribal clients as “monkeys” and “troglodytes.”

The lobbyists extended their contempt of their clients before the investigating Senate committee. Although both men were subpoenaed to be there, Scanlon did not show up, and Abramoff rejected questions, invoking the Fifth Amendment.

THE “RED” STATES—On campaign maps they are supposedly Republican strongholds. But as more of the American Indian electorate becomes active this year than ever before, that’s good news for Democrats.

The New York Times has reported that tribes with casino gambling income have contributed $4.9 million to federal political campaigns this year, 65 percent of it to Democrats. To help voter turnout, the Navajo nation, the largest tribe, with 300,000 members in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, moved its tribal government elections to November 2 to coincide with the Bush-Kerry showdown.

A particularly Indian-focused election is coming up in South Dakota, where Democratic Senator Tom Daschle, the Democrats’ Senate floor leader, is a major Republican target. Daschle may benefit from the support of one of the largest Indian populations in the nation.

The Rosebud Sioux gave Daschle the symbolic tribal honor of a red feather, granting him a chance to repeat the tribal turnout in the 2002 Congressional election. That helped give another South Dakota Democrat, Senator Tim Johnson, a 524-vote victory over John Thune, a Republican. Thune is now challenging Daschle. Daschle has campaign offices at all nine South Dakota Indian reservations.

The Democratic governor of Maine, John Baldacci, is cultivating the Pine Tree State’s Penobscot Indians. Maine is setting up and financing its Penobscot reservation as the job-creating manager, warehouser and distributor of the lower-priced pharmaceutical drugs it plans to buy in Canada for residents of Maine, barring a federal government ban on the re-importation of drugs from Canada. Excerpts from The Washington Spectator October 15, 2004 Vol. 30, #19

A Continuing Shame! New York Times Editorial Board

Native Americans came in great numbers to Washington last week, partly to celebrate, partly to correct a historic injustice. The occasion was the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall – a vivid reminder of the profound cultural and symbolic legacy of America’s indigenous peoples. In the background, however, was a continuing lawsuit, whose purpose is to restore to the Indians assets and revenues that are rightfully theirs.

Specifically, the suit seeks a proper accounting of a huge trust established more than a century ago when Congress broke up reservation lands into individual allotments. The trust was intended to manage the revenues owed to individual Indians from oil leases, timber leases and other activities. Yet a century of disarray and dishonesty by the federal government, particularly the Interior Department, whose job it is to administer the trust, has shortchanged generations of Indians and threatens to shortchange some half million more – the present beneficiaries of the trust.

Many of the beneficiaries hold minutely fractionated interests in land that has been passed down from generation to generation. But no one really grasps the true dimensions of the trust because the value of those leases and royalties is unclear, and because there has never been a real accounting of the money paid into or out of it. What has become clear is that Indians were often paid far less for leases on their property than whites were for comparable property.

Those who examine the trust – including members of Congress – come away stunned by how badly and how fraudulently it has been handled. Records have been lost and purposely destroyed. Even a conservative guess of the amount owed to Indians from the trust runs as high as the tens of billions of dollars. Ineffectual plans to reform the trust have been drawn up by the Interior Department. But instead of working to provide a historical accounting of the trust, as required, Interior officials point to concern in Congress that the cost of an accounting is likely to reach $3 billion, with no guarantee that it will actually find anything. In other words, the department wants to conclude in advance that very little is likely to be owed to anyone.

The plaintiffs have won in court every step of the way. Interior officials have repeatedly been placed under sanctions for misconduct and malfeasance. So far Interior has worked as hard to discredit the judge in the case, Royce Lamberth, as it has to actually fix the problem. The department essentially argues that the judiciary has no business telling the executive branch how to do its business. But the department has had more than a century to get this right.

These are not abstract issues. This is a case about real money owed to real people. The central question is simply: Who has profited from economic activity on the individual Indian trust lands? Certainly not the Indians who owned them. The only real reason to block a historical accounting of this trust – and real reform – is to block the real answer to that question.

FYI – For Immediate Release Contact: Peter Karafotas (202) 225-3611 Friday, October 8, 2004

REPUBLICAN SPONSORED AMENDMENT PASSES HOUSE–WAIVES FEDERAL REQUIREMENTS THAT PROTECT NATIVE AMERICAN HUMAN REMAINS, CULTURAL ITEMS AND SACRED SITES

Washington, D.C.-Today, the House of Representatives passed an amendment by a vote of 256-160, with 215 of 221 Republicans voting for the amendment that could lead to the desecration and destruction of Native American human remains, cultural items and sacred sites in the San Diego, California area. This provision will be included in the H.R. 10 – 9/11 Recommendations Implementation Act.

The amendment, sponsored by Congressman Doug Ose (R-CA), allows for the continuation of construction of a security barrier in south San Diego and waives the requirements of several laws and mandates including four that specifically and directly impact Indian tribes.These laws include: the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, the 1996 Executive Order 13007 on Sacred Sites and the Archeological Resources Protection Act Amendments of 1979.Waiving these requirements will preclude tribal and archeological notice and consultation if Native American graves are inadvertently ordeliberately disturbed or if human remains are disinterred.

“By enacting federal laws and implementing federal mandates, we promised Native Americans that we would protect and preserve their places of worship, resting places for the deceased and religious freedom. This amendment breaks that promise by not providing any mechanism for notice or consultation upon finding any cultural, ceremonial or historical sites,” said Congressman Dale E. Kildee (D-MI).from: shayne del cohen [shayne@sprintmail.com]Fri. 10/14/04

” Then there’s BLM (Bureau of Land Management). They’re terrible…..BLM comes in here to Ruby and puts on meetings. Seems they like to do a lot of promising but that’s about all. Like giving us a title to our land allotments. We did all our work filing for the 160 acres that each Native person over 18 years old was entitled to. We had to have proof that we lived there and used the land for so many years. Then file for it. They promised to give us title but seems like they been stalling us Natives off to legally own it. Four or five years now we have been hearing them promise it’ll be done next summer, next summer. We’re still hearing it” -John Honea, Athabaskan Elder – Ruby, Alaska

NYTimes.com >Opinion The Long Trail to Apology (That Never Happened!) Published: June 28, 2004

All manner of unusual things can happen in Washington in an election year, but few seem so refreshing as a proposed official apology from the federal government to American Indians — the first ever — for the “violence, maltreatment and neglect” inflicted upon the tribes for centuries. A resolution of formal apology for “a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies” has been quietly cleared for a Senate vote, with proponents predicting passage. Tribal leaders have been offering mixed reactions of wariness (“words on paper”) and approval somewhat short of delight (“a good first step”).

True, no federal reparations or claim settlements are at stake. But the rhetoric of the resolution pulls few punches about the genocidal wounds American Indians suffered in being uprooted for the New World. The Trail of Tears, the Long Walk, the Wounded Knee Massacre and other travails are specified in the resolution, which calls on President Bush to “bring healing to this land” by acknowledging the government’s offensive history.

The apology would have been received as fighting words at the Capitol in the Indian war era, when the government pursued military domination and tribes fought back. But times change, albeit very slowly sometimes, and this time it is significant that the political clout of Native Americans has never been clearer. The parties are vying for support in key political arenas, with the narrowly divided Senate particularly in play. Native Americans’ power is considerable in tribal bases like South Dakota, where their turnout was crucial in electing Senator Tim Johnson in 2002; in Alaska, where they are 16 percent of eligible voters; and in tight presidential states like Arizona, New Mexico and Nevada.

Severe health, education and economic troubles still bedevil the reservations, despite the casino riches of a minority. Accordingly, the tribes must aim for more than an apology as they pursue ambitious voter-enrollment programs. An official apology is indeed words on paper. But approval by Congress would be an acknowledgment of modern tribal power, especially if the president presented it this September at the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington.

The following is the text of S.J.RES.37, a bill to acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States, as introduced on April 6, 2004.(That Never Happened!)

JOINT RESOLUTION

To acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States.

Whereas the ancestors of today’s Native Peoples inhabited the land of the present-day United States since time immemorial and for thousands of years before the arrival of peoples of European descent;

Whereas the Native Peoples have for millennia honored, protected, and stewarded this land we cherish;

Whereas the Native Peoples are spiritual peoples with a deep and abiding belief in the Creator, and for millennia their peoples have maintained a powerful spiritual connection to this land, as is evidenced by their customs and legends;

Whereas the arrival of Europeans in North America opened a new chapter in the histories of the Native Peoples;

Whereas, while establishment of permanent European settlements in North America did stir conflict with nearby Indian tribes, peaceful and mutually beneficial interactions also took place;

Whereas the foundational English settlements in Jamestown, Virginia, and Plymouth, Massachusetts, owed their survival in large measure to the compassion and aid of the Native Peoples in their vicinities;

Whereas in the infancy of the United States, the founders of the Republic expressed their desire for a just relationship with the Indian tribes, as evidenced by the Northwest Ordinance enacted by Congress in 1787, which begins with the phrase, `The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians’;

Whereas Indian tribes provided great assistance to the fledgling Republic as it strengthened and grew, including invaluable help to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their epic journey from St. Louis, Missouri, to the Pacific Coast;

Whereas Native Peoples and non-Native settlers engaged in numerous armed conflicts;

Whereas the United States Government violated many of the treaties ratified by Congress and other diplomatic agreements with Indian tribes;

Whereas this Nation should address the broken treaties and many of the more ill-conceived Federal policies that followed, such as extermination, termination, forced removal and relocation, the outlawing of traditional religions, and the destruction of sacred places;

Whereas the United States forced Indian tribes and their citizens to move away from their traditional homelands and onto federally established and controlled reservations, in accordance with such Acts as the Indian Removal Act of 1830;

Whereas many Native Peoples suffered and perished–

(1) during the execution of the official United States Government policy of forced removal, including the infamous Trail of Tears and Long Walk

(2) during bloody armed confrontations and massacres, such as the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864 and the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890; and

(3) on numerous Indian reservations;

Whereas the United States Government condemned the traditions, beliefs, and customs of the Native Peoples and endeavored to assimilate them by such policies as the redistribution of land under the General Allotment Act of 1887 and the forcible removal of Native children from their families to faraway boarding schools where their Native practices and languages were degraded and forbidden;

Whereas officials of the United States Government and private United States citizens harmed Native Peoples by the unlawful acquisition of recognized tribal land, the theft of resources from such territories, and the mismanagement of tribal trust funds;

Whereas the policies of the United States Government toward Indian tribes and the breaking of covenants with Indian tribes have contributed to the severe social ills and economic troubles in many Native communities today;

Whereas, despite continuing maltreatment of Native Peoples by the United States, the Native Peoples have remained committed to the protection of this great land, as evidenced by the fact that, on a per capita basis, more Native people have served in the United States Armed Forces and placed themselves in harm’s way in defense of the United States in every major military conflict than any other ethnic group;

Whereas Indian tribes have actively influenced the public life of the United States by continued cooperation with Congress and the Department of the Interior, through the involvement of Native individuals in official United States Government positions, and by leadership of their own sovereign Indian tribes;

Whereas Indian tribes are resilient and determined to preserve, develop, and transmit to future generations their unique cultural identities;

Whereas the National Museum of the American Indian was established within the Smithsonian Institution as a living memorial to the Native Peoples and their traditions; and

Whereas Native Peoples are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, and that among those are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness: Now, therefore, be it

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

SECTION 1. ACKNOWLEDGMENT AND APOLOGY.

The United States, acting through Congress–

(1) recognizes the special legal and political relationship the Indian tribes have with the United States and the solemn covenant with the land we share;

(2) commends and honors the Native Peoples for the thousands of years that they have stewarded and protected this land;

(3) acknowledges years of official depredations, ill-conceived policies, and the breaking of covenants by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes;

(4) apologizes on behalf of the people of the United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States;

(5) expresses its regret for the ramifications of former offenses and its commitment to build on the positive relationships of the past and present to move toward a brighter future where all the people of this land live reconciled as brothers and sisters, and harmoniously steward and protect this land together;

(6) urges the President to acknowledge the offenses of the United States against Indian tribes in the history of the United States in order to bring healing to this land by providing a proper foundation for reconciliation between the United States and Indian tribes; and

(7) commends the State governments that have begun reconciliation efforts with recognized Indian tribes located in their boundaries and encourages all State governments similarly to work toward reconciling relationships with Indian tribes within their boundaries.

SEC. 2. DISCLAIMER.

Nothing in this Joint Resolution authorizes any claim against the United States or serves as a settlement of any claim against the United States.

Web Masters Note: It has not happened yet!

Marlon Brandon March 30, 1973 That Unfinished 1973 Oscar Speech By MARLON BRANDO

BEVERLY HILLS, Calif. — For 200 years we have said to the Indian people who are fighting for their land, their life, their families and their right to be free: ”Lay down your arms, my friends, and then we will remain together. Only if you lay down your arms, my friends, can we then talk of peace and come to an agreement which will be good for you.”

When they laid down their arms, we murdered them. We lied to them. We cheated them out of their lands. We starved them into signing fraudulent agreements that we called treaties which we never kept. We turned them into beggars on a continent that gave life for as long as life can remember. And by any interpretation of history, however twisted, we did not do right. We were not lawful nor were we just in what we did. For them, we do not have to restore these people, we do not have to live up to some agreements, because it is given to us by virtue of our power to attack the rights of others, to take their property, to take their lives when they are trying to defend their land and liberty, and to make their virtues a crime and our own vices virtues.

But there is one thing which is beyond the reach of this perversity and that is the tremendous verdict of history. And history will surely judge us. But do we care? What kind of moral schizophrenia is it that allows us to shout at the top of our national voice for all the world to hear that we live up to our commitment when every page of history and when all the thirsty, starving, humiliating days and nights of the last 100 years in the lives of the American Indian contradict that voice?

It would seem that the respect for principle and the love of one’s neighbor have become dysfunctional in this country of ours, and that all we have done, all that we have succeeded in accomplishing with our power is simply annihilating the hopes of the newborn countries in this world, as well as friends and enemies alike, that we’re not humane, and that we do not live up to our agreements.

Perhaps at this moment you are saying to yourself what the hell has all this got to do with the Academy Awards? Why is this woman standing up here, ruining our evening, invading our lives with things that don’t concern us, and that we don’t care about? Wasting our time and money and intruding in our homes.

I think the answer to those unspoken questions is that the motion picture community has been as responsible as any for degrading the Indian and making a mockery of his character, describing his as savage, hostile and evil. It’s hard enough for children to grow up in this world. When Indian children watch television, and they watch films, and when they see their race depicted as they are in films, their minds become injured in ways we can never know.

Recently there have been a few faltering steps to correct this situation, but too faltering and too few, so I, as a member in this profession, do not feel that I can as a citizen of the United States accept an award here tonight. I think awards in this country at this time are inappropriate to be received or given until the condition of the American Indian is drastically altered. If we are not our brother’s keeper, at least let us not be his executioner.

I would have been here tonight to speak to you directly, but I felt that perhaps I could be of better use if I went to Wounded Knee to help forestall in whatever way I can the establishment of a peace which would be dishonorable as long as the rivers shall run and the grass shall grow.

I would hope that those who are listening would not look upon this as a rude intrusion, but as an earnest effort to focus attention on an issue that might very well determine whether or not this country has the right to say from this point forward we believe in the inalienable rights of all people to remain free and independent on lands that have supported their life beyond living memory.

Thank you for your kindness and your courtesy to Miss Little feather. Thank you and good night.

This statement was written by Marlon Brando for delivery at the Academy Awards ceremony where Mr. Brando refused an Oscar. The speaker, who read only a part of it, was Shasheen Littlefeather. Shayne Del Cohen – Journal #302