Several articles are on this page.

Several articles are on this page.

Moving beyond the ‘imaginary Indians’ perception

By Fred Hiatt Editorial page editor of The Post. September 21 He writes editorials for the newspaper and a biweekly column that appears on Mondays.

He also contributes to the Post Partisan blog.

Kevin Gover first objected to the name of Washington’s professional football team in 1973 in a letter to then-owner Edward Bennett Williams. Williams never acknowledged the letter, Gover recalled recently, admitting that his high-schooler ‘s passion may have been a bit over the top. “I probably wouldn’t have answered that letter if I’d received it, either,” he said with a rueful smile.

Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Nation and director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, has since polished his diplomatic skills. But he well remembers the shock he felt moving here from Oklahoma with his family and suddenly encountering the name seemingly everywhere he turned. The nastiest thing people ever said to us had become the name of an NFL team? I didn’t comprehend it then, and I don’t now,” Gover said during a visit to The Post last week.

Gover is now in a position to do something about it: not to persuade the imperturbable Dan Snyder, of course, but to help other Americans understand the historical context that makes the name so offensive. And for those of us who think we get that a slur is a slur, who think we know the narrative of white expropriation from Native Americans, Gover wants to show that the historys richer and more complex than we may have been taught.

A key fact: In the early decades of the 20th century, when teams across the country were adopting Indian names and mascots, there were virtually no Native Americans left — just 250,000 in 1900. The extermination was almost complete. “There were so few that the imaginary Indians became much more real than real Indians,” Gover said. Just as whites fashioned a falsely benign history of slavery, so the textbooks portrayed a mythical version of settler-native relations. Whereas the true history was one of treaty relationships forged and then broken, and mass killings through the introduction of European diseases, Americans came to believe they had obtained their land by means of valiant conquest. Custer’s defeat at Little Bighorn became central to the narrative because it portrayed the Indian as a “formidable adversary,” Gover said, which “made it so much more heroic to inflict defeat on them.”

The Indian population has rebounded to 2.5 million tribal citizens and another 1.5 million who identify themselves as Native American without belonging to a tribe, Gover said. But for many Americans, the “imaginary Indian” still remains more real. “The textbooks seem uninterested in reviewing and revising what they say about Indians,” he said. “Teachers still teach about Pocahontas, Little Bighorn, the Trail of Tears — at best an incomplete story, and at worst incorrect.”

Now celebrating its 10th anniversary, the Indian museum on the Mall is offering one corrective in an exhibit that opened Sunday: “Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations.” Unlike past exhibits, for which the museum allowed tribes to decide which objects to exhibit, this is a fully curated, scholarly exposition, and the Smithsonian will produce classroom materials to accompany it. “We know that teachers want to get it right,” Gover said.

The exhibit shows how treaties initially were respectful documents between Indian nations, on the one hand, and vulnerable colonies and states on the other, each with something to gain through diplomacy; how they evolved as the United States strengthened and committed itself to the decimation of the tribes; and how, in the latter half of the 20th century, the treaties provided a rallying point and a legal buttress for Indians seeking to reestablish themselves. “As we’ve had a return to nation-to nation relationships, Indian country has begun to prosper again,” Gover said. Prosperity is relative, of course, and many Indian communities have a long way to go. As do white perceptions, Gover noted.

“People come into the museum and ask, ‘Where are the real Indians?’ — because I’m wearing a coat and tie,” said Gover, a Princeton grad, lawyer and former assistant secretary of the interior. For many, the only “real Indians” are on reservations, whereas “easily two-thirds of us” live in cities, he said. Which brings us back to that football team.

“One of the things that’s strange is to have Mr. Snyder lecture us on what should be important to American Indians, after a couple of carefully screened visits to reservations,” Gover said. “Those of us who’ve made a career of this can only roll our eyes, I suppose.” But what of the owner’s contention that a majority of Indians support the name? “I don’t know who those Indians are,” Gover said. “I really don’t.” SDC Journal #3208 9/25/14

An examination of the ubiquity of Indian mascots and logos. (November 1998) From: Teaching Tolerance Magazine

In popular culture, the image of the First Americans has often been reduced to caricatures and labels branding everything from cigarettes to alcoholic beverages, bed linen to children’s toys. Indeed, members of America’s Native tribal nations are often perceived by many as a culture of the past — people with little or no place in, or impact on, contemporary society.

National American Indian Heritage Month gives teachers and students an opportunity to discover the truths, triumphs and tragedies of a people who remain a vital cultural, political, social and moral presence in the constant evolution of the United States.

To help you begin this exploration, Barbara Munson, a member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, examines the ubiquity of “Indian” mascots and logos to represent school athletic teams in the following article, Not For Sport. By investigating the use of “Indian” mascots, Munson probes the misrepresentation of Native Americans and brings to light their true character.

Not For Sport

A Native American activist calls for an end to “Indian” team mascots By Barbara Munson

In April 1991 when my daughter Christine wrote a letter to her principal about her high school’s “Indian” mascot and logo, I did not realize that the issue would lead our family to activism on the state and national level. Whether the problem surfaces in New York state; Los Angeles County; Tacoma, Wash.; or Medford, Wis., I have found that it is framed by the same questions and themes.

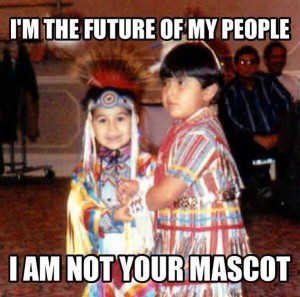

As long as “Indian” team names, mascots and logos remain a part of school athletic programs, both Native and non-Native children are being taught to tolerate and perpetuate stereotyping and racism. I would like to point out some common misunderstandings on this issue and suggest constructive ways to address them.

“We have always been proud of our ‘Indians.'”

Most communities are proud of their high school athletic teams, yet school traditions involving Native American imagery typically reflect little pride in or knowledge of Native cultures. These traditions have taken the trappings of Native cultures onto the athletic field where young people have played at being “Indian.” Over time, and with practice, generations of children in these schools have come to believe that their “Indian” identity is more than pretending.

“We are honoring Indians; you should feel honored.”

Native people are saying that they don’t feel honored by this symbolism. We experience it as no less than a mockery of our cultures. We see objects sacred to us — such as the drum, eagle feathers, face painting and traditional dress — being used not in sacred ceremony, or in any cultural setting, but in another culture’s game.

Among the many ways Indian people express honor are: by giving an eagle feather, which also carries great responsibility; by singing an honor song at a powwow or other ceremony; by showing deference toward elders, asking them to share knowledge and experience with us or to lead us in prayer; by avoiding actions that would stifle the healthy development of our children.

While Indian nations have the right to depict themselves any way they choose, many tribal schools are examining their own uses of Indian logos and making changes. Native American educators, parents and students are realizing that, while they may treat a depiction of an Indian person with great respect, such respect is not necessarily going to be accorded to their logo in the mainstream society.

“Why is an attractive depiction of an Indian warrior just as offensive as an ugly caricature?”

Both depictions uphold stereotypes. Both firmly place Indian people in the past, separate from our contemporary cultural experience. It is difficult, at best, to be heard in the present when someone is always suggesting that your real culture only exists in museums. The logos keep us marginalized and are a barrier to our contributing here and now.

Depictions of mighty warriors of the past emphasize a tragic part of our history; focusing on wartime survival, they ignore the strength and beauty of our cultures during times of peace. Many Indian cultures view life as a spiritual journey filled with lessons to be learned from every experience and from every living being. Many cultures put high value on peace, right action and sharing.

“We never intended the logo to cause harm.”

That no harm was intended when the logos were adopted may be true. It is also true that we Indian people are saying that the logos are harmful to our cultures, and especially to our children, in the present. When someone says you are hurting them by your action, then the harm becomes intentional if you persist.

“Aren’t you proud of your warriors?”

Yes, we are proud of the warriors who fought to protect our cultures from forced removal and systematic genocide and to preserve our lands from the greed of others. We are proud, and we don’t want them demeaned by being “honored” in a sports activity on a playing field.

Indian men are not limited to the role of warrior; in many of our cultures a good man is learned, gentle, patient, wise and deeply spiritual. In present time, as in the past, our men are also sons and brothers, husbands, uncles, fathers and grandfathers. Contemporary Indian men work in a broad spectrum of occupations, wear contemporary clothes, and live and love just as men from other cultural backgrounds do.

The depictions of Indian “braves,” “warriors” and “chiefs” also ignore the roles of women and children. Many Indian Nations are both matrilineal and child-centered. Indian cultures identify women with the Creator, because of their ability to bear children, and with the Earth, which is Mother to us all. In most Indian cultures the highest value is given to children — they are closest to the Creator and they embody the future.

“This logo issue is just about political correctness.”

Using the term “political correctness” to describe the attempts of concerned Native American parents, educators and leaders to remove stereotypes from the public schools trivializes a survival issue. Systematic genocide over four centuries has decimated more than 95 percent of the indigenous population of the Americas. Today, the average life expectancy of Native American males is 45 years. The teen suicide rate among Native people is several times higher than the national average. Stereotypes, ignorance, silent inaction and even naïve innocence damage and destroy individual lives and whole cultures. Racism kills.

“What if we drop derogatory comments and clip art and adopt pieces of ‘real’ Indian culture, like powwows and sacred songs?”

Though well-intended, these solutions are culturally naïve and would exchange one pseudo-culture for another. Powwows are religious as well as social gatherings that give Native American people the opportunity to express our various cultures and strengthen our sense of Native community.

To parody such ceremonial gatherings for the purpose of cheering on the team at homecoming would compound the current offensiveness. Similarly, bringing Native religions onto the secular playing field through songs of tribute to the “Great Spirit” or Mother Earth would only heighten the mockery of Native religions that we now see in the use of drums and feathers.

“We are helping you preserve your culture.”

The responsibility for the continuance of our cultures falls to Native people. We accomplish this by surviving, living and thriving; and, in so doing, we pass on to our children our stories, traditions, religions, values, arts and languages. We sometimes do this important work with people from other cultural backgrounds, but they do not and cannot continue our cultures for us. Our ancestors did this work for us, and we continue to carry the culture for the generations to come. Our cultures are living cultures — they are passed on, not “preserved.”

The responsibility for the continuance of our cultures falls to Native people. We accomplish this by surviving, living and thriving; and, in so doing, we pass on to our children our stories, traditions, religions, values, arts and languages. We sometimes do this important work with people from other cultural backgrounds, but they do not and cannot continue our cultures for us. Our ancestors did this work for us, and we continue to carry the culture for the generations to come. Our cultures are living cultures — they are passed on, not “preserved.”

“Why don’t community members understand the need to change; isn’t it a simple matter of respect?”

On one level, yes. But in some communities, people have bought into local myths and folklore presented as accurate historical facts. Sometimes these myths are created or preserved by local industry. Also, over the years, athletic and school traditions grow up around the logos. These athletic traditions can be hard to change when much of a community’s ceremonial and ritual life, as well as its pride, becomes tied to high school athletic activities.

Finally, many people find it difficult to grasp a different cultural perspective. Not being from an Indian culture, they find it hard to understand that things that are not offensive to themselves might be offensive or even harmful to someone who is from a Native culture. Respecting a culture different from the one you were raised in requires some effort — interaction, listening, observing and a willingness to learn.

We appreciate the courage, support and, sometimes, the sacrifice of all who stand with us by speaking out against the continued use of “Indian” logos. When you advocate for the removal of these logos, you are strengthening the spirit of tolerance and justice in your community; you are modeling for all our children thoughtfulness, courage and respect for self and others.

Barbara Munson, a member of the Oneida Nation who lives in Mosinee, Wisc., is chairperson of the Wisconsin Indian Education Association “Indian” Mascot and Logo Taskforce.

From: Teaching Tolerance Magazine

Image Source: Fact Source: Barbara Munson, “Not for Sport,” and Cornel Pewewardy, “Beyond the ‘Wild West,’ ” Teaching Tolerance (Spring 1999).

Look for additional articles: Lewis & Clark, Culturally Responsive Curriculum, ABC’s of Thanksgiving in our Teachers Page Links.